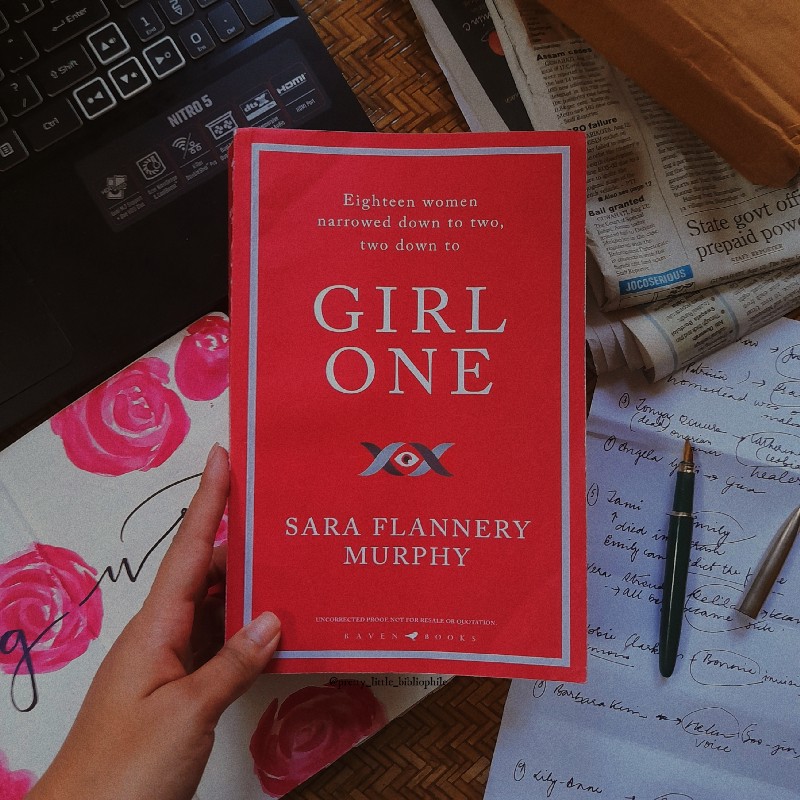

One of my major reads of August was Girl One by Sara Flannery Murphy, and I was just blown away by the epiphanies that I had while reading it. In hindsight, I think this is a really dystopian (or ‘utopian’ if you’d rather) take on a feminist fantasy — that of a possible world without men.

Before delving deeper, I have to say that I received a copy of this book from the publishers, but all the thoughts that I will be sharing today are entirely my own and in no way influenced by others.

For your consideration, here is what Goodreads describes it as:

Orphan Black meets Margaret Atwood in this twisty supernatural thriller about female power and the bonds of sisterhood. Josephine Morrow is Girl One, the first of nine “Miracle Babies” conceived without male DNA, raised on an experimental commune known as the Homestead. When a suspicious fire destroys the commune and claims the lives of two of the Homesteaders, the remaining Girls, and their Mothers scatter across the United States and lose touch.

Years later, Margaret Morrow goes missing, and Josie sets off on a desperate road trip, tracking down her estranged sisters who seem to hold the keys to her mother’s disappearance. Tracing the clues Margaret left behind, Josie joins forces with the other Girls, facing down those who seek to eradicate their very existence while uncovering secrets about their origins and unlocking devastating abilities they never knew they had.

Before we begin — I do not need you to come at me saying “Not all men!”

— I KNOW.

A Compelling Authorial Voice

Authority and authenticity reigned supreme in this fictional work and perhaps that is why it was so easy to imagine this was true and happening right now in the vast expanse of the United States.

From the very beginning, we are given a trail of crumbs to follow — each revelation pulls the reader deeper and deeper, all the while giving multiple shocks and unexpected twists.

Since this book also dealt with such important themes, even a slight mishandling of the pace could have disrupted the intended effect. And so in that regard, I have to applaud the excellent pacing as well — it was fast and hurtled the reader on a journey across the states in an endeavor to find Josephine’s mother, and at the same time, it provided these pockets of time where the characters were suspended in a world of their own, to form relations of their own.

Male Gaze and Male Ownership (and the Fragile Male Ego)

Girl One also revolved a lot around the male gaze. Even though we see the world from Josephine’s eyes, the first ‘miracle baby’, it is essentially a world created by the male ambition as well as the male influence.

A man trying to come into the picture to take credit for something he did not do, doesn’t sound very far-fetched, does it?

Especially when it was a woman whose work he wants to take credit for.

In fact, it sounds like something that may have happened to someone you know, or maybe even you! We have all experienced it — be it with classmates, colleagues, or acquaintances.

Girl One really takes on this male need to control and possess the knowledge and take credit (even where it’s not due). As such it is a fabulous piece of feminist discourse within the fictional aspect.

This need to control and overtake and dominate and own, anything ‘weaker’ or ‘lesser’ in their eyes is so vehement, so aggressive. It happens here too, in this book, and we as readers are left reeling by the epiphanies.

What was also funny and at the same time, made me theorize and introspect, was how the men in the world portrayed in Girl One felt threatened by this parthenogenesis (self-reproduction) in women.

Their question was, if women no longer needed men to procreate, what would be their place in the world? What would happen to the family structure without the father/male figure?

What it indirectly showed was how they felt threatened — that their positions would now be useless? That may be, history would be created and written by women? That with this re-writing of history, all the oppression that women had faced at the hands of men (emotional, political, social, sexual, mental, physical, and so on), would come out to light?

Or was it all a cumulative reflection of the fragile male ego?

Sisterhood and Womanhood

Reading this book made me remember the term ‘Womanism’ that I came across some time ago. Sisterhood is such an important theme in this book and I loved seeing the relationships among the women.

Then again, it is not always sunshine and roses (as those of us with sister siblings can testify) and I am glad the author chose to portray all the bad along with the good.

But nonetheless, without negating the importance of this, we need to draw our attention to intersectional feminism to take into account the multiple jeopardies that the world places political bodies in.

The Sci-Fi Element

The scientific temperament that was explored was also, really cool to imagine.

Just think —a world where women are able to conceive on their own, without the need for sperms.

What would a world like that entail?

I recently had also read the short story ‘Sultana’s Dream’ by Rokeya Sahkawat Hossain, so it was quite easy for me to imagine this ‘utopian’ dream of a world with only women.

Similar Recommendations

If you are still wondering whether you should read this book, let me say that if you have read any of the below-mentioned three books, you SHOULD!

- The Power, by Naomi Alderman

- The Girls, by Emma Cline

- The Handmaid’s Tale, by Margaret Atwood

Alternatively, if you have read Girl One and liked it, you can also check out these books!

And that is it for today, my fellow readers. If you have read this book and have an opinion (similar or contrary), do share because I would love to know your perspective. If you haven’t read the book, I hope I have convinced you to pick it up and give it a chance.

Nayanika Saikia graduated summa cum laude with a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature and was also a Dean’s List student. She is currently pursuing her Master’s degree and is also a Booktuber and Bookstagrammer. She can often be found on her Instagram account Pretty Little Bibliophile. You can support her by Buying Her a Coffee. To get regular updates and amazing content, sign up for her newsletter.

Stuck for what to read next? Check out our Reading Recs page. And if you’d like to support our work, please consider making a donation via our Donations page. We’re trying to raise money for paid commissions, so we can support and work with more writers from underrepresented backgrounds, who cannot afford to write for free. Thank you for reading!